On February 16, 2023, Australia’s Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) publicised its Review Report, the latest output in the Privacy Act 1988 review process that began in 2020. The report seeks to strengthen the Act, while retaining the flexibility of its principles-basis. One core motivation is to bring the Privacy Act closer to other international standards and data regulations, such as the GDPR. Although more needs to happen before the Report’s proposals become enacted laws, they have emerged during a period of significant data breaches (e.g., the Optus breach, the Medibank breach, and the Latitude Financial breach), which can only accelerate the tightening-up process.

The Report puts forward a long list of recommendations aimed at reforming the Privacy Act and enhancing data privacy measures. These recommendations can be grouped into 3 categories:

1. Broadening the Scope of the Privacy Act

What is Personal Information?

Despite the adoption of guidance on the concepts of personal information, the AGD notes that there is still confusion about the remit of the Privacy Act. The AGD mentions confusion about “whether technical information that records service details about a device is the personal information of the owner of the device” and whether “inferred information about an individual, for example in an online profile, will be personal information.” The identifiability test is also not always well understood in practice. Stakeholders participating in the review process have asked for clarity about “how to ‘reasonably identify’ an individual and correspondingly how to know when an identifiable individual becomes ‘de-identified.’”

Without surprise, the AGD proposes to adopt a broad definition of personal data, which should include both technical and inferred information: “personal information includes technical information, inferred information and any other information where that information relates to the individual, in the sense it can be seen to provide details about their activities or their identity and the connection is not too tenuous or remote.” By way of example, personal information could include:

- name, date of birth or address

- an identification number, online identifier, or pseudonym

- contact information

- location data

- technical or behavioural data in relation to an individual’s activities, preferences, or identity

- inferred information, including predictions of behaviour or preferences, and profiles generated from aggregated information

- one or more features specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, behavioural, economic, cultural or social identity or characteristics of a person

Such a broad definition is said to align with other standards like the GDPR.

There is also an intention to clarify the concept of sensitive information, which should extend to genomic information. Precise geolocation tracking data should also benefit from additional protection. It is made clear that sensitive information can be inferred from information that is not sensitive but is used as a proxy for the sensitive information.

The Report also proposes to provide enhanced privacy protections for employees of the private sector. Employees’ personal information should be protected from misuse, loss, or unauthorised access, and should be destroyed when it is no longer required. Both employees and the Information Commissioner should be notified of any data breach involving employee’s personal information which is likely to result in serious harm.

When is Information De-Identified?

Although we already have guidance on data de-identification, covered entities continue to struggle with the standards around this process.

The Review Report suggests a twofold approach:

- To encourage the use of de-identified information by reducing the regulatory burden when covered entities process de-identified information.

- To ensure that covered entities that are handling de-identified information internalize the privacy risks associated with this information. This would be achieved by applying the Privacy Act selectively and in particular by applying APP Principles 8 and 11.1 to de-identified data.

As a result, covered entities would thus be subject to the following obligations:

- “to take such steps as are reasonable in the circumstances to protect de-identified information: (a) from misuse, interference and loss; and (b) from unauthorised re-identification, access, modification or disclosure.”

- “when disclosing de-identified information overseas to take steps as are reasonable in the circumstances to ensure that the overseas recipient does not breach the Australian Privacy Principles in relation to de-identified information, including ensuring that the receiving entity does not re-identify the information or further disclose the information in such a way as to undermine the effectiveness of the de-identification.” The Report is also considering introducing a relative prohibition on reidentification.

Should Small Businesses be Subject to the Privacy Act?

The answer is yes. The Report proposes to remove the small business exemption once a comprehensive package of assistance is developed to minimize compliance costs for these entities. This would mean that all Australian businesses would have to comply with the Privacy Act, regardless of annual turnover. One argument put forward in favor of the removal of this exemption was the absence of a small business exemption in the GDPR itself, which had made negotiations about adequacy status challenging in the past.

2. Strengthening and Clarifying the Obligations Imposed upon Covered Entities

The Report proposes to amend the act to introduce “a requirement that the collection, use and disclosure of personal information must be fair and reasonable in the circumstances,” irrespective of whether consent has been obtained. It is also proposed that the “test should be an objective test to be assessed from the perspective of a reasonable person,” therefore not recommending the incorporation of the concept of legal basis to be found in the GDPR.

Also included are proposals to enhance intervenability by strengthening existing rights, such as the right to access or the right to correction, and the granting of a range of new rights to individuals so that they benefit from greater transparency and control. These include the right to object, to erasure, to delist search results, to request meaningful information about how substantially automated decisions with legal or similarly significant effect are made, to opt-out from direct marketing, targeted advertising, and to opt-in to the trading of one’s personal information. Covered entities are asked to provide reasonable assistance to individuals when they exercise their rights under the Act. Some practices are prohibited such as trading in the personal information of children, targeting a child or targeting individuals based upon sensitive information and transparency requirements are strengthened.

From a data security standpoint, the Report calls for the production of enhanced guidelines which should clarify what reasonable steps are to secure personal information under APP 11.1 and destroy or de-identify personal information under APP 11.2. There is also a strong emphasis on data retention: both minimum and maximum retention periods should be spelled out and periodically reviewed.

In addition to the obligations set forth in APP 1, the Report proposes to include an express requirement to determine and record the primary and secondary purposes for which personal information is processed. The Report also proposes to expand the remit of security obligations set forth in APP 11.1 to de-identified data, and suggests introducing the distinction between controller and processor and a mechanism to prescribe countries with substantially similar protection to the APPs in the context of international transfers along with the possibility to resort to standard contractual clauses. Privacy Impact Assessments also find their way into the Report for activities with high privacy risks.

3. Solidifying and Streamlining Data Breach Enforcement

One central goal pursued by the Report is to increase the range of enforcement mechanisms. It thus proposes to introduce tiers of civil penalty provisions and clarify what “serious interferences” are. It also recommends that the Information Commissioner is provided the power to undertake public inquiries and reviews into specified matters on the approval or direction of the Attorney-General, and to require a respondent to take reasonable steps to mitigate future loss in case of data breach. This makes the case for granting broader powers to the Federal Court when making civil penalty orders.

Most notably, the Report recommends the introduction of a direct right of action in order to permit individuals to apply to the courts for relief in relation to an interference with privacy, as well as the introduction of a statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy.

Regarding data breaches more specifically, a first step had been accomplished with the Privacy Enforcement Act passed on 28 November 2022, which increased civil penalties. The Report seeks to further tighten the notifiable data breaches scheme, and proposes a detailed timeline: a notification to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (‘OAIC’) should take place within 72 hours and then a further notification as soon as practicable to the individuals to whom the information relates.

Covered entities are recalled of the importance to implement data breach response plans through the introduction of an express provision to this effect, and it is proposed to force entities making statements about an eligible data breach to set out the steps they’ve taken or intend to take in response to the breach, including, where appropriate, steps to reduce any adverse impacts on the individuals to whom the relevant information relates.

Main Takeaways from the Review Report

Of the many proposals and stipulations included in the recent Review Report, the main changes to Australian privacy law can be distilled into three main takeaways:

- Covered entities under the Australian Privacy Act should prepare for the “big shift.” They should carefully review their data classification and make sure they are able to govern the entire data lifecycle, from collection to de-identification or destruction, passing by transfer to third countries.

- They should put in place robust privacy programmes, recording processing activities, organizing them by purpose on the basis of a detailed data retention schedule, and provisioning access on the basis of the need-to-know principle. In addition to data segmentation, data obfuscation and de-identification should systematically be explored to further reduce the attack surface of the organisation.

- Covered entities should also implement effective data breach detection and response plans, with a view to put themselves in a position to demonstrate that they have taken proactive measures to both prevent and reduce adverse impacts on individuals in cases in which a breach materializes.

Achieving Compliance with the Immuta Data Security Platform

To effectively meet the compliance requirements created by these regulatory updates, organisations need tools that enable a range of privacy-enhancing measures. With the Immuta, teams can strengthen their data ecosystem through the application of the following data security and privacy methods:

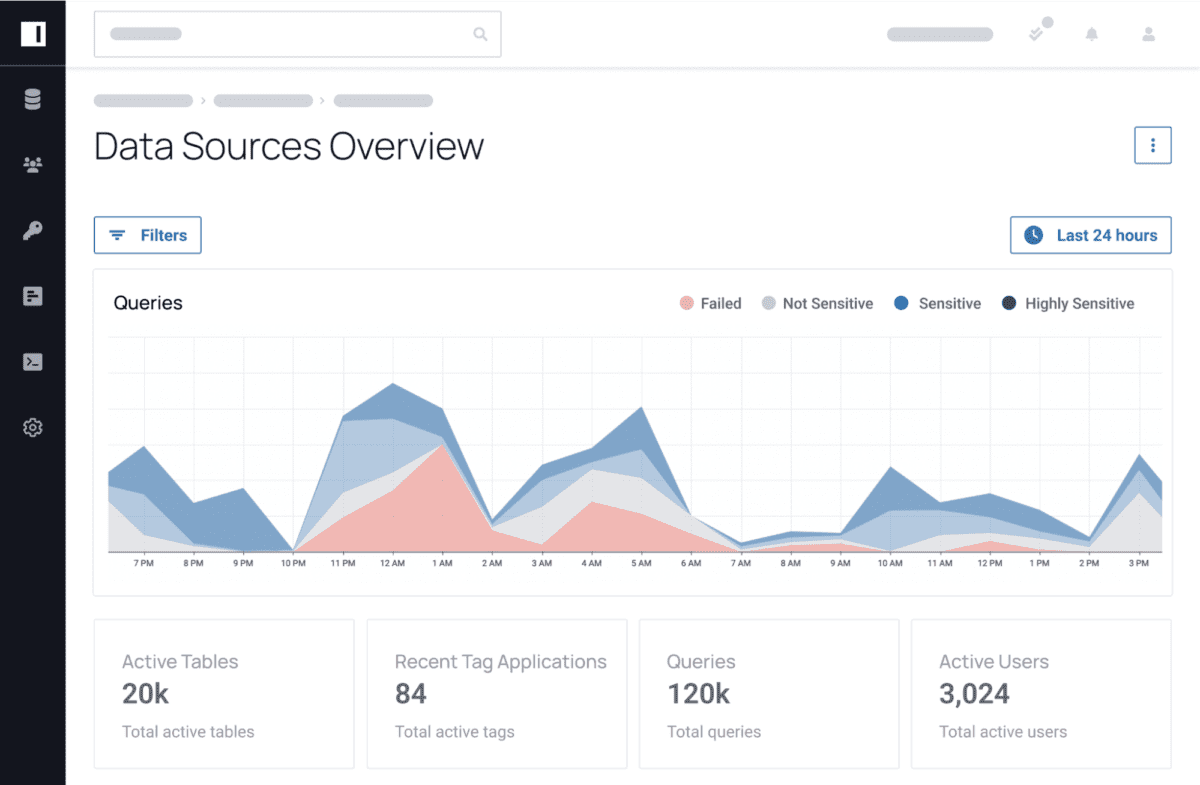

Data Discovery & Classification

Immuta applies data discovery to any and all sensitive data in an ecosystem, automatically scanning, tagging, and classifying this information and providing teams with insight into the types and sensitivity levels of the data they possess. With sensitive personal information tagged appropriately, teams can then take the necessary measures to ensure the continued privacy and security of the data.

Data Access Governance

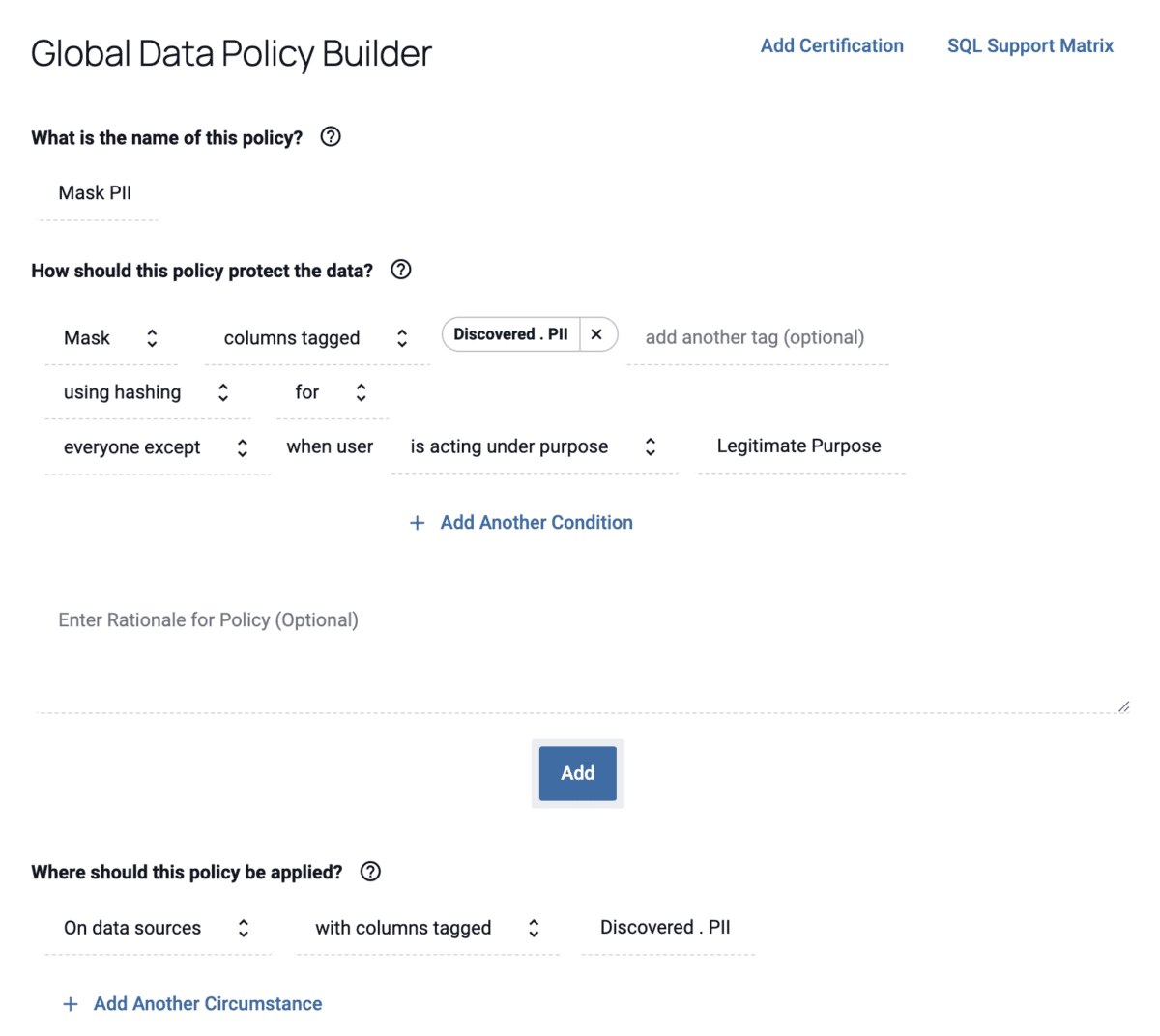

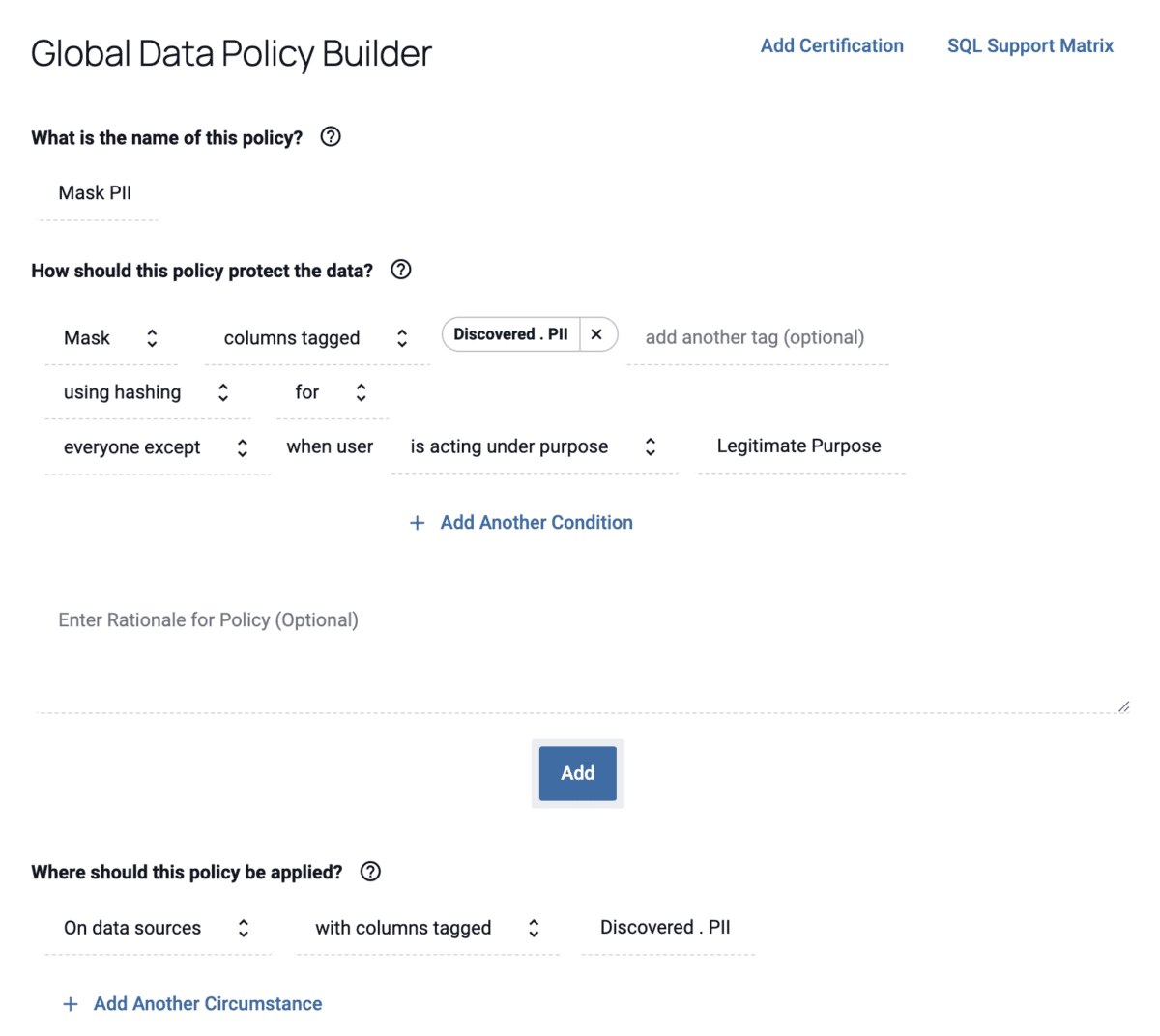

With Immuta, teams can apply dynamic data masking to tagged sensitive data in order to de-identify the information and protect individuals’ privacy. Using attribute-based access control policies, teams can apply access and governance controls to any data query without restricting utility for data users who require access. Policies are written in plain language and can be adjusted at any time, allowing teams to ensure compliance with any changing regulations.

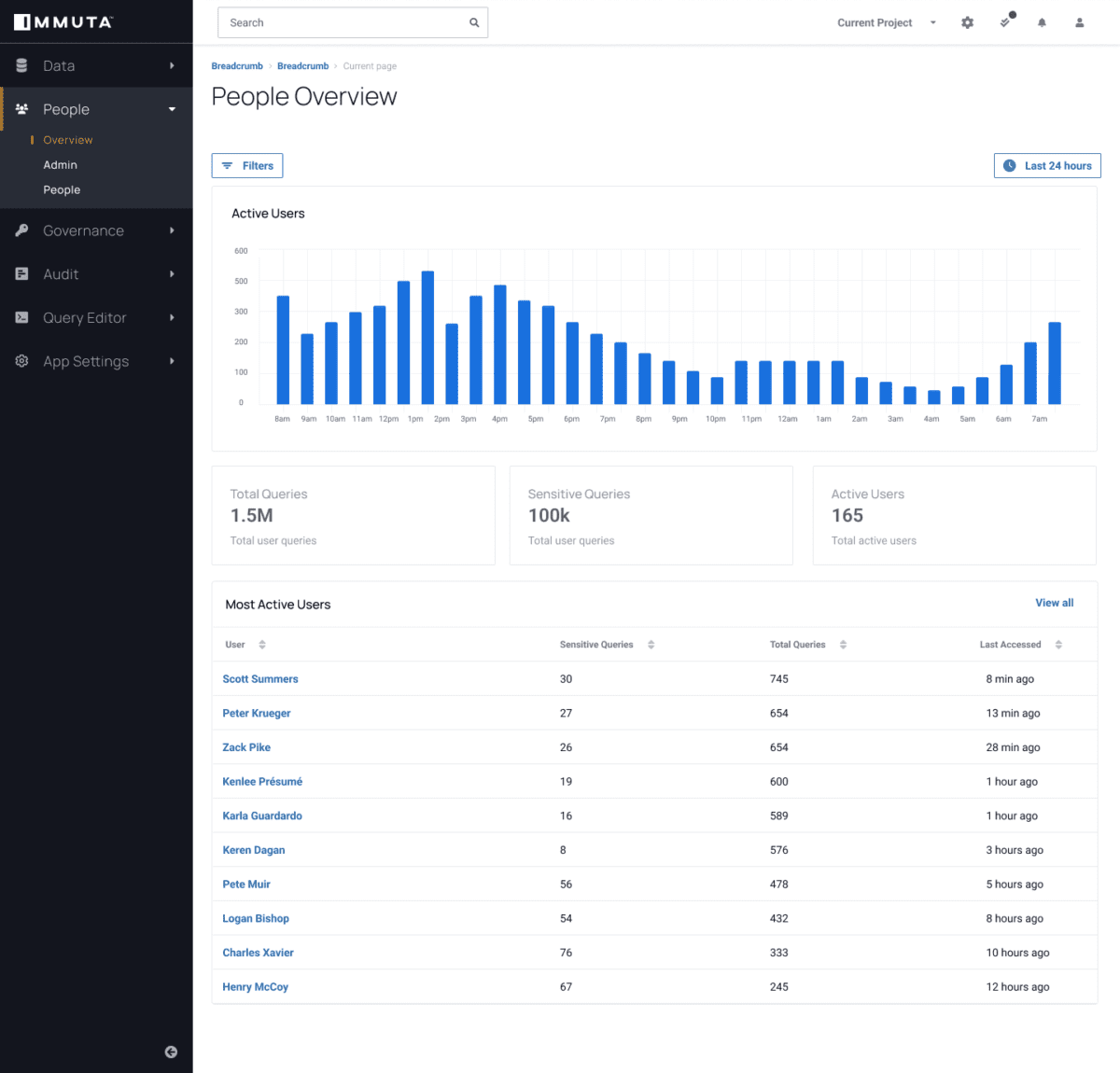

Unified Auditing

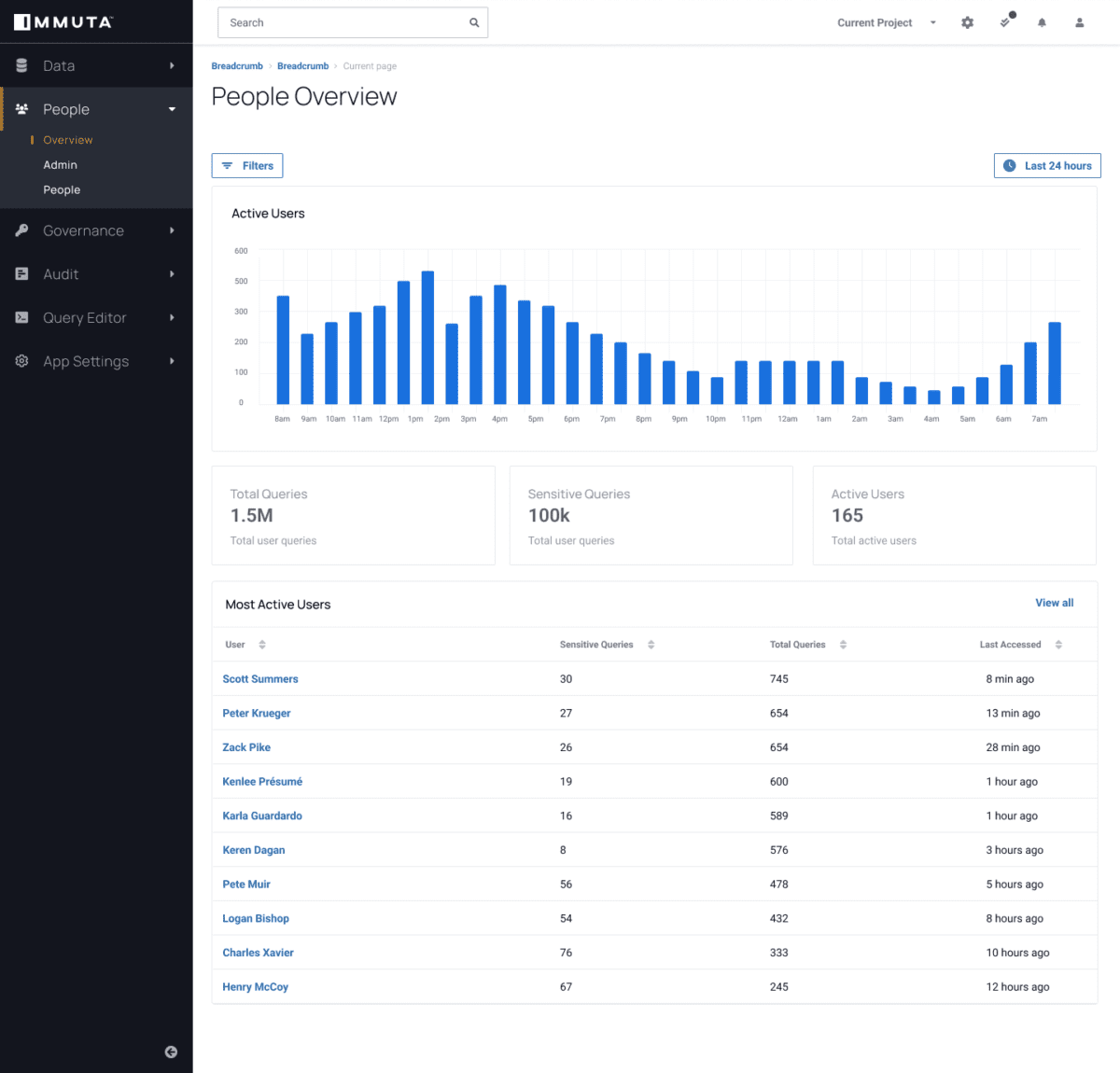

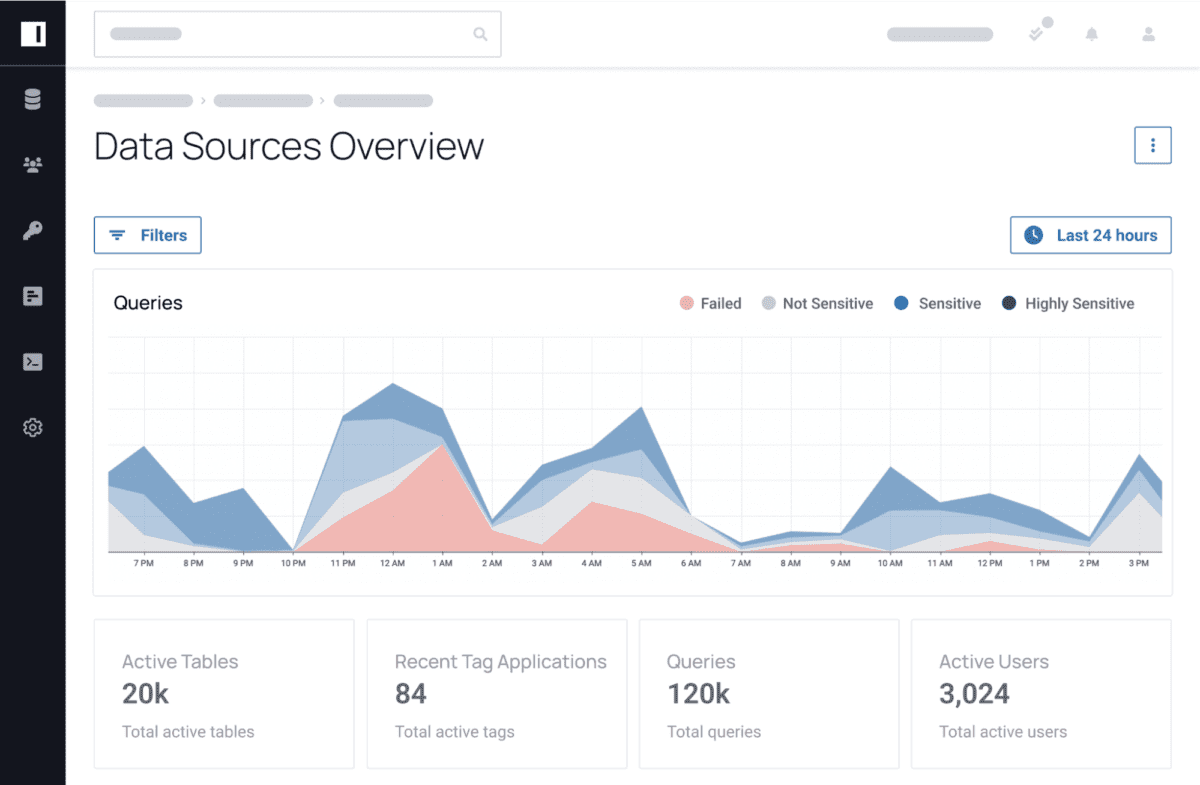

To impose the required oversight across a data ecosystem, Immuta enables teams with consistent data monitoring and detection capabilities. Through activity monitoring and posture management, teams have a real-time view of the activity on their data and are notified instantly of any suspicious activity or breach. This helps organisations to achieve the most immediate response to any form of leak or breach.

Learn more about APRA data security standards and how Immuta can help achieve compliance. To see it for yourself, request a demo with one of our experts.

Unlock Safe and Secure Data

Talk with our team.